This Space Available

By Emily Carney

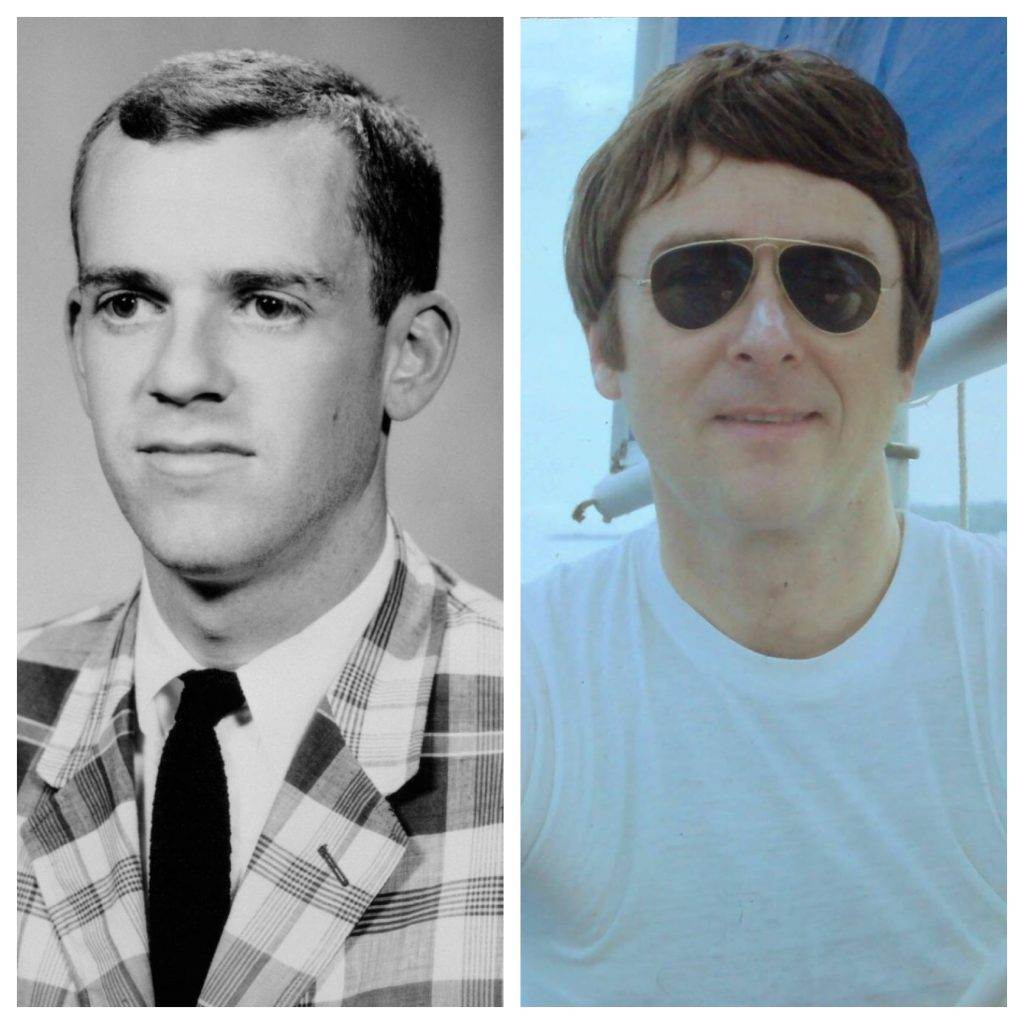

During this past year, This Space Available has profiled Dr. Brian O’Leary, perhaps the most (in)famous and controversial ex-NASA astronaut, and Dr. Gerard K. O’Neill, a physicist who, while not quite making it to O’Leary’s astronaut group, still enjoyed a diverse career and a type of cult-like fame throughout the 1970s with the publication of his classic treatise about space settlement, The High Frontier. During the decade, their orbits (pardon the pun) intersected; they enjoyed the apex of their friendship mid-decade, when O’Leary was brought on as a faculty member at Princeton, O’Neill’s home base since the 1950s.

While, as we saw, their partnership would grind to a halt as O’Leary’s “inner space began to stir” (his words) and he became increasingly enamored with New Age ideas that were often criticized as anti-science by former colleagues, both scientists independently left their imprints upon pop culture during the 1970s, the decade in which they both were most publicly visible. O’Leary, unsurprisingly, gained no friends at NASA for his 1970 book The Making of an Ex-Astronaut, was roundly trounced in reviews, and continued to do himself no favors by writing a series of op-eds that were seen as hostile to his former employer. However, he arguably also kept himself in the spotlight with his activities, and maintained a media presence throughout the decade. In contrast, O’Neill, who was frequently described as “soft-spoken” and professorial, perhaps gained the most surprising amount of fame, and appeared in publications as family-friendly as People, and as niche as…Penthouse.

O’Leary, King of the (Not Always Appreciated) Op-Ed

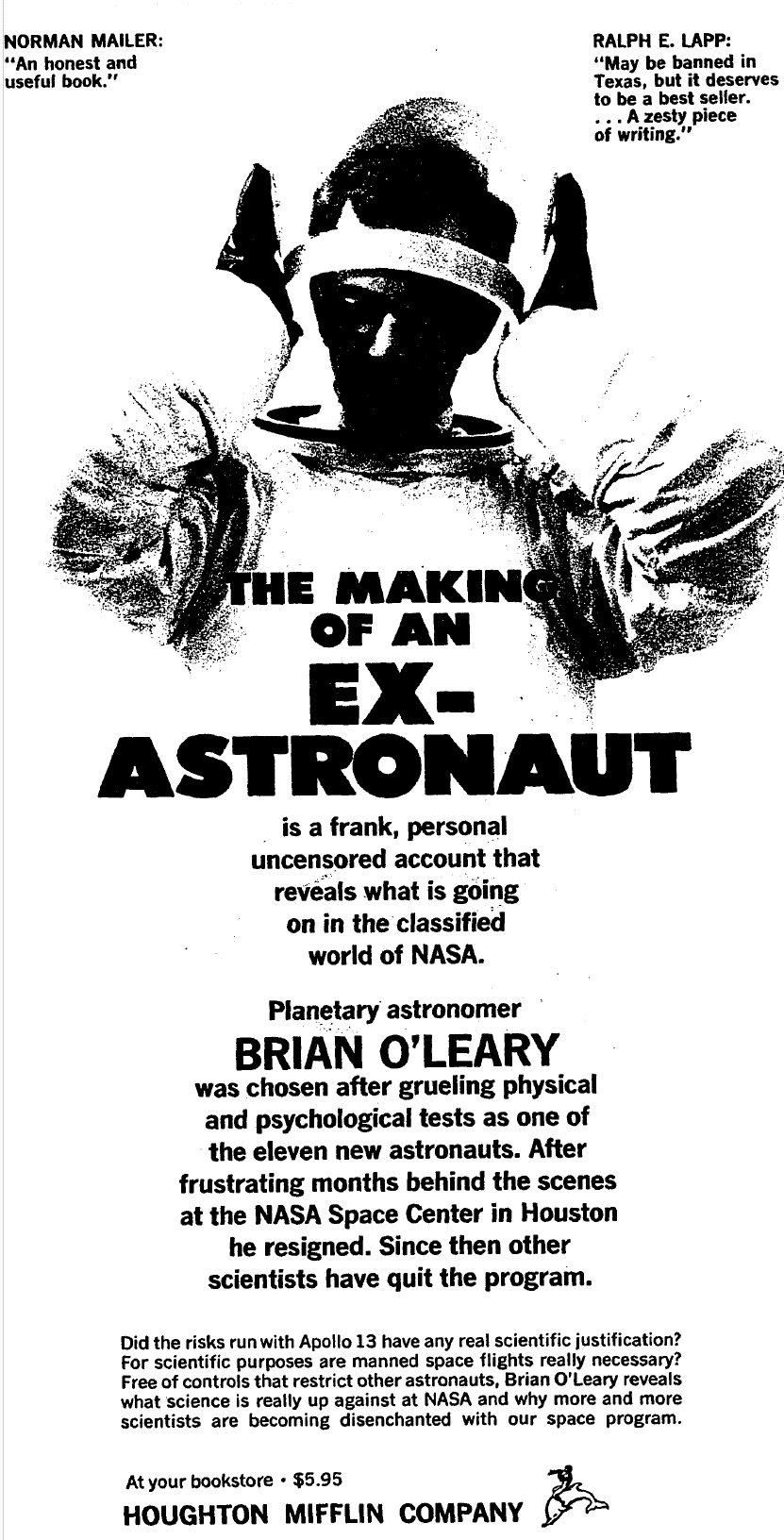

In spring 1970, Houghton Mifflin published O’Leary’s The Making of an Ex-Astronaut, which functioned as a sort of autobiography interspersed with the author’s opinion about NASA’s then-current path, and the future of human spaceflight. While O’Leary made many incisive (and still relevant) observations about Apollo’s lack of focus upon scientific objectives near the book’s end, and described his time at the space agency with brutal (some would say embarrassing) honesty, his views were not appreciated by both NASA brass and former colleagues. A May 5, 1970 review of Ex-Astronaut by NASA’s Robert B. Voas in The Washington Post captured what many in the aerospace world thought of the book, and its anti-hero protagonist. Voas described the book’s depictions of its author’s fellow astronaut group colleagues as “limited” (indeed, O’Leary did resort to describing Dr. Philip Chapman, who by 1967 was a formidable scientist with Antarctic exploration experience, as a “penguin” and “a limp pancake”), and concluded at the end that NASA still has a lot to learn about selecting scientist astronauts with the line, “It is all very sad.”

Another piece from Reuters, published on May 17 that year, is entitled “Stafford Rips ‘Pseudo-Hippie’ Ex-Astronaut,” and focuses on “Space man Tom Stafford” (as he is described in the article) and his unhappiness with O’Leary’s book. Rather hysterically, Stafford called O’Leary “a pseudo-hippie” and “a malcontent,” and particularly took issue with the ex-astronaut’s (rather long and drawn out, chapter length) hatred of Houston. Stafford is quoted as saying, “I have found Houston to be one of the most dynamic and growing cities in the United States…The people are absolutely wonderful and all of us have come to like this city as much as our hometowns.” Indeed, then-Houston Mayor Louis Welch, also angered by O’Leary’s depiction of his kingdom (O’Leary: “An undesirable place to live…like the Amazon jungle plus smog”), claimed in the piece he “read O’Leary’s comments first with anger, then with contempt, and finally with sympathy.” This move by Stafford seems, in part, an attempt by NASA brass to mitigate any ill will generated by O’Leary’s overwhelmingly negative comments about the city.

A half-page advertisement for the book that ran inThe New York Times on the same day tried to capitalize humorously upon O’Leary’s extended hatred of Houston. A blurb by Ralph E. Lapp stated, “May be banned in Texas, but deserves to be a bestseller…A zesty piece of writing.” Another blurb was supplied by none other than famous literary stalwart Norman Mailer, whose Of A Fire On The Moon still elicits mixed responses. Mailer described Ex-Astronaut as: “An honest and useful book.”

Uncompromisingly honest, O’Leary would continue to channel his talents for arousing outrage among former colleagues with a series of op-eds written for The New York Times. On April 25, 1970, the newspaper published a piece with his byline entitled “Topics: Science – Or Stunts – On The Moon?” While O’Leary did make some cogent points about how science was considered to be a lesser priority during Apollo, the op-ed’s publication right after the near-disastrous Apollo 13 and right before the publication of Ex-Astronaut could be viewed as bad timing. On June 5, 1973, O’Leary would publish another op-ed for the same paper called “Pie In The Sky,” which levied criticism at the upcoming Space Shuttle program, and even took some rather ill-timed swipes at embattled space station Skylab, which in previous weeks had sustained severe damage upon launch.

This piece, for obvious reasons, also did not go over well with the spaceflight community, even though O’Leary had made some persuasive points about cost overruns at NASA. While the Space Shuttle program would prove to be spectacular and ultimately very useful, it would face delays until April 1981, and was more expensive than advertised. Two former XS-11 astronaut colleagues, Dr. Joe Allen and Dr. Karl Henize, would write a rebuttal to O’Leary’s op-ed in a letter to the editor titled “Space: Mankind Must Have A Dream,” and O’Leary responded back with his rebuttal to their letter later that summer. Again, his words – however well-meaning and correct he may have believed they were – created controversy among the astronaut cadre.

By mid-decade, O’Leary would publicly waver back and forth regarding his support of the nascent Space Shuttle, and – almost surprisingly – worked extensively alongside O’Neill, who proposed methods to settle space utilizing Shuttle hardware. Tune in to the next installment of This Space Available, in which O’Neill’s pop culture impact will be explored, and we’ll also discover how the quiet, affable Princeton professor somehow ended up becoming one of the only fully-clothed people in the August 1976 issue of Penthouse.

Some of this piece was derived from “Just Like Starting Over”: O’Leary’s Startling New Direction, written by this author on September 21, 2019. Many thanks to Alan Andres for helping with research for this piece.

*****

Emily Carney is a writer, space enthusiast, and creator of the This Space Available space blog, published since 2010. In January 2019, Emily’s This Space Available blog was incorporated into the National Space Society’s blog. The content of Emily’s blog can be accessed via the This Space Available blog category.

Note: The views expressed in This Space Available are those of the author and should not be considered as representing the positions or views of the National Space Society.

Featured Photo Credit: Dr. Brian O’Leary 1967 passport photo, at left, retrieved from the National Archives; Dr. Gerard K. O’Neill, pictured during the 1970s, at right – photo from The High Frontier: The Untold Story of Gerard K. O’Neill Facebook page, supplied by SSI/O’Neill’s family.