This Space Available

By Emily Carney

In the previous installment of This Space Available, Dr. Philip Chapman brainstormed one of the Apollo program’s most famous televised experiments, resigned from NASA’s astronaut corps following the cancellation of Skylab B, and entered into a post-NASA career that saw him rubbing elbows with Dr. Gerard K. O’Neill. In this concluding installment, we’ll return to the place where his scientific career began, undoubtedly one of the closest analogues to another planet that exists on Earth: Antarctica. Moreover, we’ll catch up with him at present time.

Flashback: 1957 – 1958

But first, we’re going to time travel to Chapman’s first experiences at the South Pole, which happened shortly after he graduated from Sydney University. In 1957, the young man who would become the first Australian selected to the astronaut cadre was frustrated at his day job, low on funds, daydreaming about coming to the United States to pursue his dreams of spaceflight, and actively searching for a way out of his circumstances. In his words:

I was a space nut from age 12. After I graduated from Sydney University in 1956, I wanted to come to the United States and get involved, but I had no money. I took a job at Dutch Philips in Sydney, but I was quite frustrated. In early 1957 I saw an ad from ANARE (Australian National Antarctic Research Expeditions), seeking volunteers to winter at Mawson Station in 1958 (the International Geophysical Year). It certainly sounded more interesting than my job at Philips, so I applied – but my usual procrastination meant that the team had been chosen. ANARE suggested I apply again the following year.

Sputnik 1 was launched in [October 1957], which meant that the space age was really here, but I was still stuck in Sydney. One morning just before Christmas, I received a phone call in my lab at Philips from Fred Jacka, the chief scientist at ANARE in Melbourne, He said that one of their physicists for 1958 had broken his leg. Could I fill in? Damn right.

Chapman had roughly ten minutes to break the news to his boss at Dutch Philips, and also had to break the news to a girlfriend:

The ship would sail in a week, and I would need some orientation, issue of gear, etc. – so could I possibly be in Melbourne that evening? A plane ticket would be waiting at the airport. So I gave ten minutes notice to my boss and went to see my girlfriend (who also worked at Philips) to tell her I would be back in 15 months. She was not pleased. Ten days later I was on iceberg watch on the bridge of the MV Thala Dan, in the monstrous seas of the Southern Ocean. I was 22, and I had never been out of sight of land.

There were 29 of us at Mawson, all male. My job was to study the aurora australis. To that end, a two-man camp had been established the previous year at Taylor Glacier, 50 miles west of Mawson. The idea was to take stereo photos of the aurora (which is at an altitude of about 60 miles), using a camera mounted on a theodolite. I spent most of the winter there.

My companion was replaced about every two weeks, using one of two DH Beavers at Mawson. They landed on the sea-ice, usually about a mile from shore.

A principal attraction was that most of the nameless nunataks (rocky hills) nearby had never been climbed, and a first ascent got your name on it (mine is called Chapman Ridge).

Chapman also was able to interact with some of the region’s natural habitats in ways that could not be done at present time:

Another tourist attraction was that the camp was in a gully adjacent to an Emperor penguin rookery with about 5,000 birds. Like almost every animal in Antarctica they were very tame. I have a photo somewhere of Henry Fischer, our cook from Mawson, standing on an actual soapbox, giving a political rant to the penguins, in German (Henry was Swiss). They were not impressed.

Access to the rookery is now restricted to biologists, but we had no such constraints. I don’t believe socializing with the Emperors ever did them any harm.

The original hut at Taylor was blown away in a blizzard, so we lived in a packing crate, about seven by seven by nine feet. It was guyed down to anchors in the rocks, but it bounced around a lot when the wind got up. There was no daylight near midwinter, the temperature was about 40 degrees Celsius below zero, and the wind was often over 100 knots. It was a formative experience.

The aurora was a mystery when I went to Antarctica, but the first US satellite, Explorer 1, discovered the Van Allen Belts while I was there. Physicists everywhere understood the lights in the sky – except for those of us who had been observing them, out of touch in Antarctica.

In 1958, most of Antarctica had never been seen, even from the air. It was possible to speculate that over the next hill we would find a valley, heated by volcanism, where dinosaurs still survived (as in Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Lost World). The satellites took out a lot of the romance.

Chapman’s early Antarctic experience also marked his entry into the world of spaceflight, as he was able to save up enough funds to finance his educational aspirations. In addition, Chapman arguably was the first astronaut hopeful to take part in a “space analogue” of sorts, given that the space environment has similarities to the Antarctic, which undoubtedly made him more attractive to NASA in 1967:

I was very fortunate to have had this opportunity to winter in Antarctica. It was of course a fascinating adventure, but also there was nothing to spend money on at Mawson, so my salary accumulated for 15 months. That funded a move to Boston, where I found a research job at MIT that let me earn my doctorate – and I am sure that having the Antarctic on my resume impressed the NASA astronaut selection committee.

A Return to Extreme Climates, 1977 – 1989

Despite the 1972 end of his astronaut career, his forays into spaceflight and extreme environments were far from over. According to a capsule autobiography in his novel Strike on the Ice: An Antarctic Adventure (published in 2017, and available on Amazon), in 1977 Chapman “served as a pilot for an airborne sortie to investigate a glacial lake on Baffin Island [in Canada] that had not previously been visited, even by the Inuit.” This coincided around the time he left Avco and began working for Dr. Peter Glaser, who also worked extensively with Dr. Gerard K. O’Neill to bring Glaser’s ideas of solar power satellites to fruition, and around the time he became president of the L5 Society. In 1989, he would return to the place that gave him experience in out-of-this-world climates, and initially funded his scientific career:

In 1989 I led a privately-funded expedition to the area around Taylor Glacier, using an ice-strengthened ocean-going tug that we rented in Cape Town [South Africa]. We built a helideck on the long aft deck of the tug, with a hangar for two helicopters.

The objective was to look into possible mineral resources, especially gold, before prospecting was banned in the upcoming Madrid Protocol to the Antarctic Treaty. That agreement, signed in 1991, imposed draconian environmental restrictions on all aspects of Antarctic expeditions.

I was especially opposed to the effective prohibition of economic activities, specifically including mining. As in human spaceflight, I believed (and still do) that Antarctic research would eventually have to pay its way, with appropriate safeguards. We didn’t know what resources were there, and we wouldn’t find out if we didn’t go look.

I often hear that the Antarctic environment is very fragile, but I would call it ferocious, and more resistant to human intervention than any place on Earth. It is a very large continent, with 75% more area than the contiguous United States. Most of it is covered by ice, but there are lots of rocky areas on the coasts and mountains inland. Prohibiting all mining is as silly as worrying that a mine in Montana would damage Miami.

Chapman’s second Antarctic expedition wasn’t without adversity; according to Colin Burgess’ book Shattered Dreams, ice blocked his group’s transit when they were about 42 miles from their destination, and the crew had to make their way to shore via helicopter. But, they made it:

We didn’t expect that finding valuable minerals would start a gold rush, because the conditions are too difficult, but I was aware that it might have derailed the Madrid Protocol. Unfortunately, we didn’t find gold, or anything else in commercial quantities, but it was a great adventure.

The Present Time

In more recent years, Chapman was chief scientist for the rocket startup Rotary Rocket Company, was chair of the Solar High Study Group, has enjoyed writing, and perhaps owing to his marked modesty, has stayed away from the autograph and public appearances circuit enjoyed by other space personalities. Shattered Dreams did underscore how his presence as the first Australian-born astronaut paved the way for other Aussies in spaceflight; for example, oceanographer Dr. Paul Scully-Power launched into space aboard Challenger in 1984, and Australian-born Andy Thomas would prove to be a perennial flier during the Shuttle years. Within the last decade, Australia has even established its own space agency, giving the Southern continent a bigger international profile; Australia has notably never had a shortage of “space geeks,” and many of them are active in a plethora of social media groups dedicated to spaceflight.

Some former scientist-astronauts retained bitterness about their experiences at late 1960s and early 1970s NASA. Brian O’Leary wrote an entire book about how flying planes, Houston in general, and NASA just wasn’t his cup of tea. Curt Michel of NASA’s first scientist-astronaut group relayed some bitterness about portrayals of him by other astronauts, especially Walt Cunningham and Deke Slayton, within the pages of Burgess’ and David Shayler’s book NASA’s Scientist-Astronauts. But despite Chapman’s sometimes less-than-happy time at NASA, and the fact that he left before he could make a spaceflight, he approached his own situation with equanimity.

In Shattered Dreams, Chapman related, “I have enjoyed an adventurous, rewarding life. I am of course sorry I didn’t get into space, but that experience would have been just one more trinket on my string of memories.” Ever the futurist, he added, “What is deeply frustrating is that NASA betrayed the dream, and that means I shall not live to see our society liberated from the constraints of this fragile little planet.” Indeed, Chapman is excited about the advent of private companies entering into spaceflight; in our interview, he stated, “I thank God (or Elon Musk) that we are now seeing the beginning of private enterprise in human spaceflight.”

Pioneering Antarctic explorer, scientist, first Australian-born astronaut, and unsung space visionary, Dr. Philip Chapman has certainly earned his name in the canon.

Catch up on Parts One and Two of this series:

First Aussie: Dr. Philip Chapman, Apollo’s Astronaut from “Down Under,” Part One

First Aussie: Dr. Philip Chapman, Apollo’s Astronaut from “Down Under,” Part Two

Many thanks to Colin Burgess and Francis French for assistance with research; also deepest thanks to Dr. Philip Chapman, who agreed to be interviewed for this series.

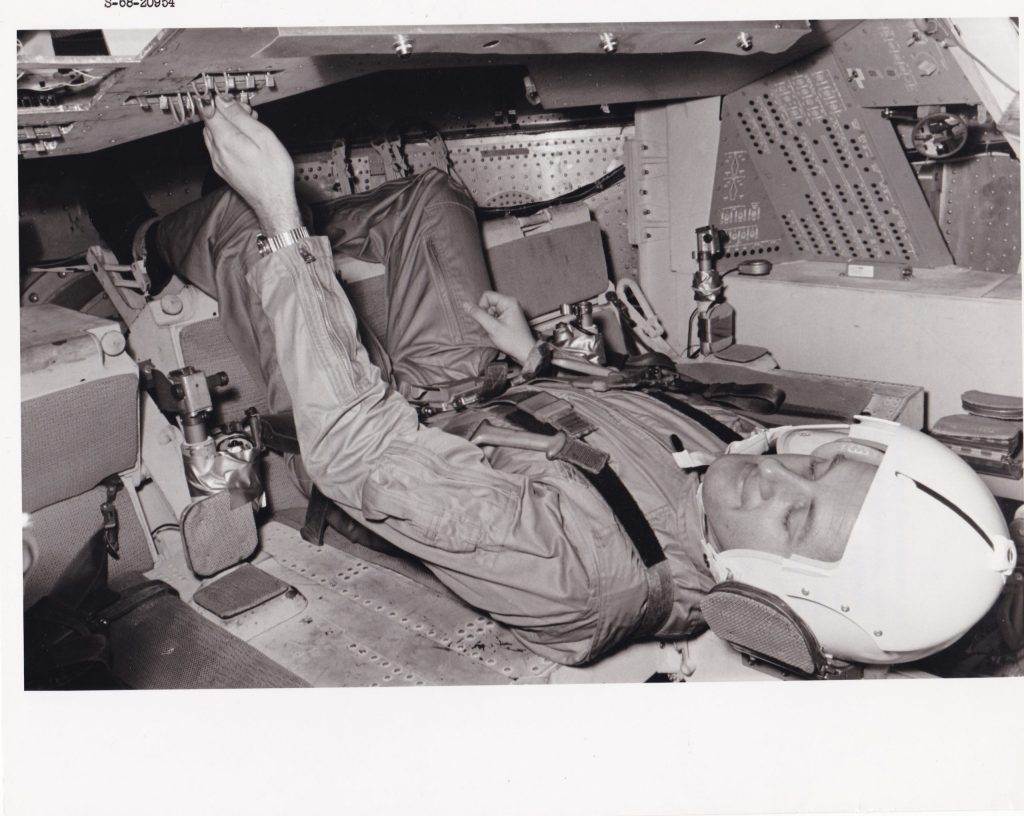

Featured Photo Credit: Always in command – “In the gondola of the MSC centrifuge in the FAF Building,” circa 1968. Photo and caption supplied by Colin Burgess.

*****

Emily Carney is a writer, space enthusiast, and creator of the This Space Available space blog, published since 2010. In January 2019, Emily’s This Space Available blog was incorporated into the National Space Society’s blog. The content of Emily’s blog can be accessed via the This Space Available blog category.

Note: The views expressed in This Space Available are those of the author and should not be considered as representing the positions or views of the National Space Society.