This Space Available

By Emily Carney

Once upon a time…

At this point in our story, the mid-Seventies were in full swing at NASA, and preparations for the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project were well in gear. In late 1974, NASA was already laying the groundwork for its next big space endeavor, the Space Transportation System – better known as the Space Shuttle, the delta-winged “space truck” that was conceptualized to serve as dual low-cost cargo freighter, and high-tech science platform. Human-helmed, long-duration Skylab space station missions, which were comprised of all-male crews, had ended in February that year. The European space program, not yet named ESA, was beginning to formulate its vision for a German-built onboard lab that would be nestled within the Shuttle’s payload bay. And with this new program in development, a new kind of astronaut-scientist would be needed.

This program, Spacelab, would require on-Earth verification; according to the book NASA’s Scientist-Astronauts by David J. Shayler and Colin Burgess, “At the Marshall Space Flight Center (MSFC) in Huntsville, Alabama, a Concept Verification Test (CVT) programme was assembled on 25 July 1973, with the aim of simulating high data-rate experiments on the ground to test data compression techniques. These also included data interaction and onboard processing.” The TDRS system would need to be in place before Spacelab missions flew, ensuring high data rates could be ably captured; the ATS-6 satellite would be used as a test platform for that program during Apollo-Soyuz in July 1975.

A high-fidelity mock up of Spacelab was assembled at MSFC during 1974, and according to Shayler and Burgess, “[a] Preliminary Requirements Review for the new simulator was held on 29-30 May 1974.” This test program would enable “participation by principal investigators who were developing potential experiments for Spacelab missions. This would allow them to test hardware, techniques, and interfaces in order to verify their operation prior to assignment to specific missions.”

As soon as the CVT program Spacelab mock up was completed, there was little delay in getting its Earth analogue missions underway. The history of Earth analogue missions is a subject this author needs to explore in greater detail, but three notable ones held during the late 1960s and early 1970s, sanctioned by NASA, included LTA-8 (crewed Lunar Module test, 1968), 2TV-1 (crewed Command Module test, 1968), and the Skylab Medical Experiment Altitude Test (abbreviated SMEAT, 1972). These “missions” were all male, boasting astronaut names including Jim Irwin, Joe Engle, Joe Kerwin, Vance Brand, and perennial Shuttle flier Bob Crippen, to name a few.

But one Spacelab analogue, held from December 16 through 21, 1974, was crewed by all women…moreover, all women scientists. Shayler and Burgess wrote, “CVT Test No. 4…was a five-day simulated Spacelab mission with eleven materials sciences experiments that the four female crew members had developed. These four women, all employees of Marshall Space Flight Center, were Ann F. Whitaker, Carolyn S. Griner, Mary Helen Johnston, and Doris Chandler.”

The inclusion of four women scientists in this 1974 Earth analogue flies in the face of some erroneous reporting and attitudes that there were no women “qualified” to fly into space until 1978, when the first six women were, at long last, selected to NASA’s astronaut corps. As this author wrote in a Space Review piece published earlier this year, “There was no real reason why women were excluded from eligibility as Apollo astronauts…There were women scientists and engineers who existed during the 1960s who, if they had been allowed to enter Air Force flight training, likely could have qualified as pilots next to male astronaut-scientist colleagues, and therefore could have met astronaut qualifications. If scientists like Harrison Schmitt could qualify to fly on Apollo, there is no reason that women could not.” Likewise, if a solar physicist such as Dr. Ed Gibson could qualify to fly a long-duration Skylab mission, there was no reason that similarly qualified women could not.

But back to CVT Test No. 4. Shayler and Burgess continued, “This simulation provided a wealth of data on the benefits of having a scientifically trained crew aboard the facility to identify and repair minor malfunctions. In a 1976 report of this test, it was stated: ‘The value of the well trained scientist crew was emphasized during the test. Had it not been for the extremely knowledgeable science crew, two experiments at least would have been lost early in the simulation. [They] were saved by their knowledge of both the hardware and the science that was to be obtained.’”

The CVT program would last through 1976, but fell victim – not surprisingly – to mid-1970s budget cuts. These analogue missions would also hardly be the end of Spacelab simulations (for more information about the entirety of Spacelab, please read NASA’s Scientist-Astronauts and NASA History’s publication Spacelab: An International Short-Stay Orbiting Laboratory). The first actual Spacelab mission, STS-9, wouldn’t launch until late 1983, and the first woman aboard a Spacelab flight wouldn’t fly until 1985 (Dr. Bonnie Dunbar, aboard October 1985’s STS-61A/Spacelab D1 mission).

More sadly, none of the women of the fourth CVT test would fly in space, although Dr. Mary Helen Johnston would come the closest, having been selected as a reserve payload specialist for the STS-51B Spacelab 3 mission. Carolyn Griner, who joined MSFC in 1964, according to NASA, would become “the Acting Director of the NASA Marshall Space Flight Center from January 3, 1998 to September 11, 1998, between the terms of the eighth and ninth Directors. Before and after her term as Acting Director, she was Deputy Director of the Marshall Center.” Whitaker also went on to have a successful career, according to NASA: “Over a 16-year period Dr. Ann Whitaker served at NASA as chief of the Physical Sciences Branch, the Engineering Physics Division, and the Project and Environmental Engineering Division. In 1995 she served in several leadership positions in Marshall’s Science and Engineering Directorate. In September 2001, Dr. Whitaker was named director of the Science Directorate at MSFC.”

CVT Test No. 4 lasted only five days, and only a handful of incredible photos linger from this late 1974 sojourn when women scientists more than proved their mettle. However, this short mission left powerful resonances. At present time, astronaut Megan McArthur is in the midst of a long-duration mission aboard the International Space Station (ISS), and a number of women astronaut-scientists have flown – and flourished – aboard the Space Shuttle, the Mir space station, and the ISS. Current Earth analogue missions – including HI-SEAS – now show that these type of simulations must be inclusive.

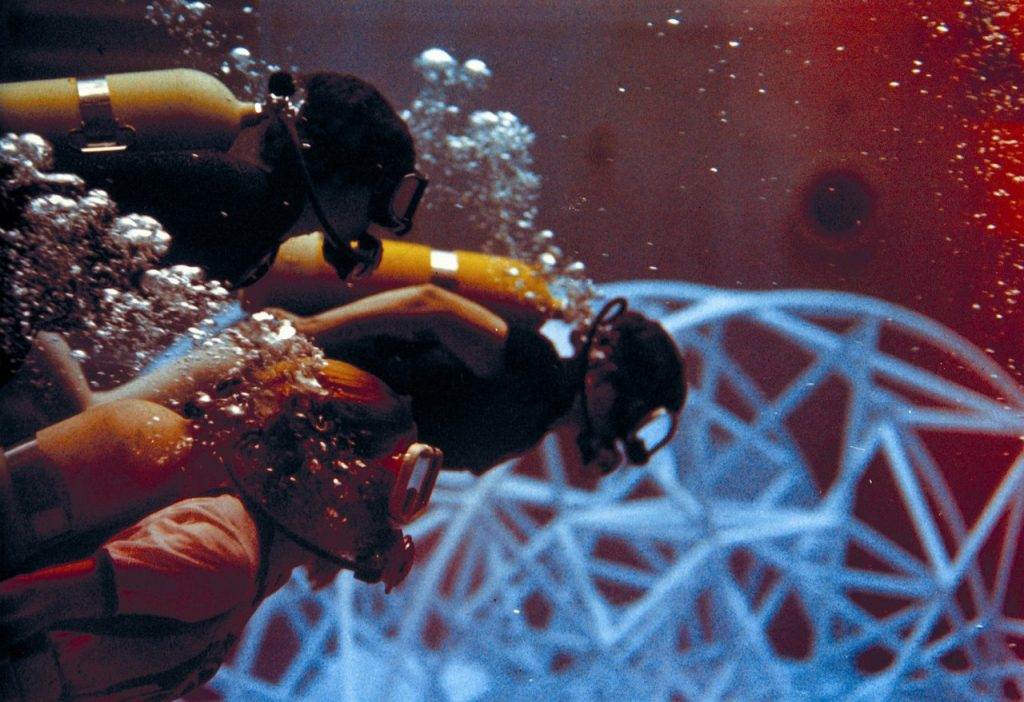

Featured Photo Credit: “Women scientists in training at Marshall Space Flight Center, (top to bottom) Carolyn Griner, Ann Whitaker, and Dr. Mary Johnston, are shown simulating weightlessness while undergoing training in the Neutral Buoyancy Simulator. These women were part of a special program dedicated to gaining a better understanding of problems involved in performing experiments in space. The three were engaged in designing and developing experiments for space, such as materials processing for Spacelabs. Dr. Johnston specialized in metallurgical Engineering, Dr. Whitaker in lubrication and surface physics, and Dr. Griner in material science. Dr. Griner went on to become Acting Center Director at Marshall Space Flight Center from January to September 1998. She was the first woman to serve.” (NASA photo)

*****

Emily Carney is a writer, space enthusiast, and creator of the This Space Available space blog, published since 2010. In January 2019, Emily’s This Space Available blog was incorporated into the National Space Society’s blog. The content of Emily’s blog can be accessed via the This Space Available blog category.

Note: The views expressed in This Space Available are those of the author and should not be considered as representing the positions or views of the National Space Society.

4 thoughts on “Space in the Seventies: Spacelab and the Dawn of Women Astronaut-Scientists”

Another fine article on a forgotten portion of our history. Emily, I’m wondering about the ladies SCUBA activities. I’m guessing that after they were certified by NASA in the giant hot tub there, they might have taken up the sport in ernest in waters around Texas and Florida. It would be interesting to hear how their possible adventures in the Silent World might have affected their work later at NASA.

Informative article!! Thanks for covering this aspect of Spaceflight!!

Space flight was dangerous. What man does not shrink from the idea of sending a woman into danger? As things improved and greater safety, though not total safety, came to be accepted it became easier in the hearts of the men to include women. Perhaps it is an instinctive thing in human species that we men must protect the women because it is from them that succeeding generations come. Now I know it is unfashionable to say such things and I know some will sneer “Is all you want us for?” Not “all” of course, but instincts of protection run deep.

It seems when science and politics meet, politics win.