This Space Available

By Emily Carney

Apollo 9’s Russell “Rusty” Schweickart began the 1970s with a quest to figure out why he’d suffered from unwelcome bouts of space sickness aboard his March 1969 Earth orbital flight. After submitting himself to a series of taxing and frankly uncomfortable medical tests, he and NASA researchers couldn’t figure out what made him (or anyone else, as we now know space sickness occurs in about half of space travelers) more susceptible to the phenomenon than, say, fellow crew member Dave Scott. Schweickart thought (not incorrectly) that it probably would’ve helped him and other colleagues if Apollo 8 commander Frank Borman had been more forthcoming about his space sickness experiences. His tenacious research into space sickness was rewarded with…absolutely zilch, nothing, and nada, as he was not slated to be on the prime crew of any upcoming spaceflights.

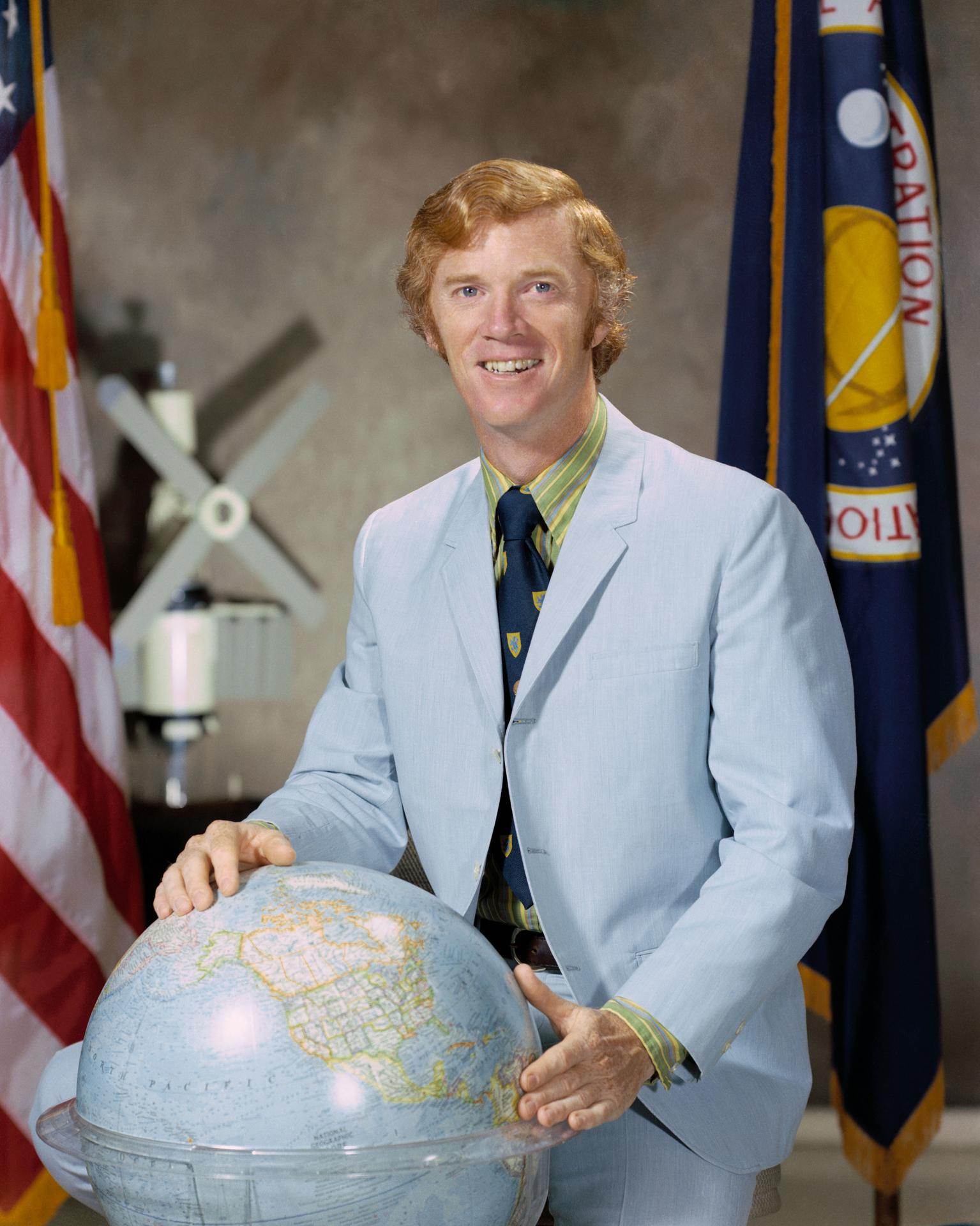

But no matter. The redheaded Schweickart always had stood out among the NASA astronaut cadre as a truthteller and more of a “scientist” than an engineer/pilot, which wasn’t always appreciated. In Colin Burgess and Francis French’s book In the Shadow of the Moon: A Challenging Journey to Tranquility, 1965 – 1969, he stated, “…One thing if you know me, whether it sits smoothly or not, you get the truth. I don’t play games. I’m a very straightforward person, and I probably see the world a bit more simply than it is. Other people sometimes see subtleties that I just overlook, but it isn’t my nature to play games.”

He knew his refusal to be blindly obedient didn’t always gain him supporters. He knew he was a bit of an outcast and a rebel among the crowd who sported crewcuts; by this point, he’d grown his hair out to a length some of his more conservative colleagues found unacceptable. There weren’t many – okay, real talk, there were zero – other Apollo-era astronauts who extolled the virtues of transcendental meditation and an interconnectedness with the Earth that Frank White would later christen the “overview effect.”

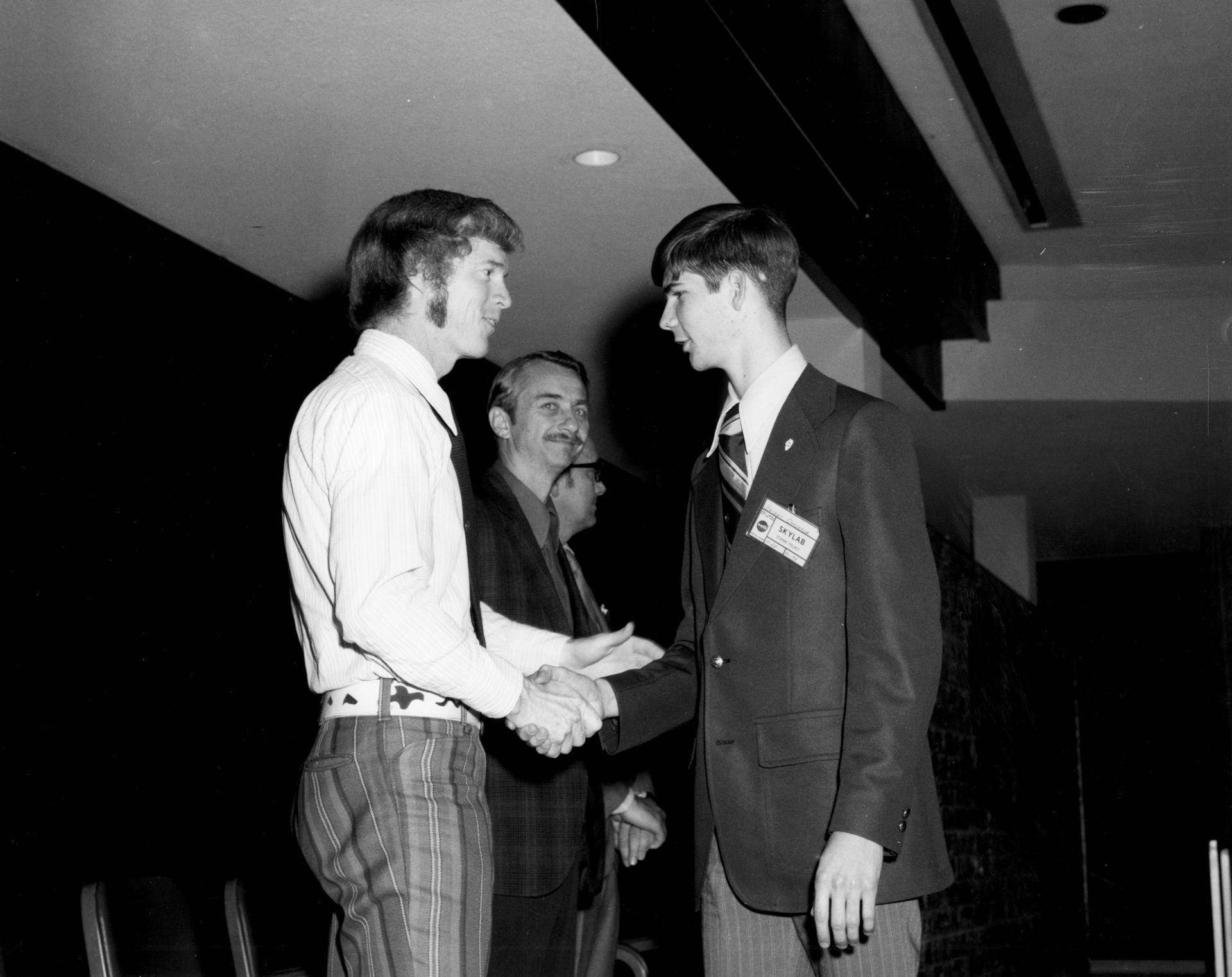

His views on, say, international diplomacy differed from those of his colleagues; when the Association of Space Explorers (ASE) was being established during the 1980s, he and fellow longhaired ex-astronaut Al Worden nearly came to blows over matters of world peace (the entire hysterical story is recounted in Worden’s memoir The Light of Earth, which you really should read). A 1974 New York Times article by Molly Ivins entitled “Ed Who?,” ostensibly about Skylab 4’s apple-pie-cheeked, definitely not hippie-ish science pilot Dr. Ed Gibson, left no stone unturned when it came to how “Red Rover” stood out compared to his fellow astronauts:

Rusty Schweickart has earned himself a reputation as a radical (everything’s relative—about half the male employees at the space center still wear crewcuts). A few years ago, the Pacifica radio station in Houston, a free‐wheeling, listener‐sponsored outlet that permitted all manner of hairy radicals and black militants to use its air time twice had its transmission tower blown up by the Ku Klux Klan. Schweickart came to the rescue, helping to raise money for the station, going on the air and being generally helpful. “He’s the closest thing there is to a freak astronaut,” said Larry Lee, former station manager at Pacifica Houston.

As the early 1970s progressed, his fellow Apollo 9 crew members Jim McDivitt and Dave Scott took expected roles in NASA management. McDivitt spent his silver fox years as the Apollo program manager until he retired in 1972; Scott was rewarded with the command of Apollo 15 and became the eventual chief of Dryden (now Armstrong) Flight Research Center, where he remained until his 1977 retirement. But Schweickart stayed true to form and forged more unorthodox paths during his 1970s career, starting with his criminally underrated Skylab work.

Skylab and Landsat

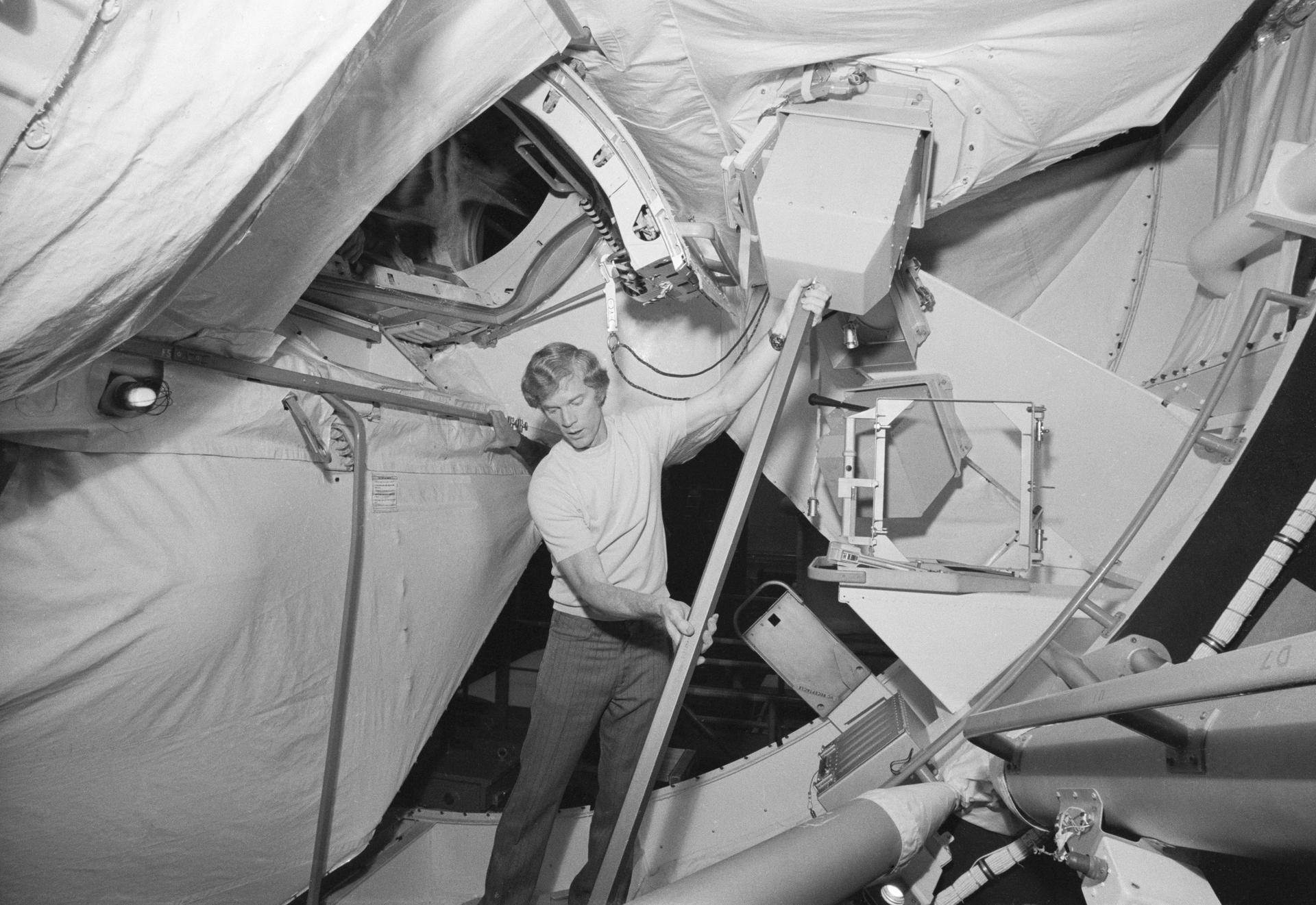

On May 14, 1973, the Skylab space station launched from Kennedy Space Center on the Apollo program’s final Saturn V but was in peril only a minute into its flight when it lost its micrometeoroid shield and, minutes later, SAS-2 solar panel; the station’s remaining solar panel was jammed by debris. Over ten days, NASA mobilized its efforts to save its first space station from scorching temperatures and power deficits. One of the figures at the forefront of this effort was Schweickart, who served as Skylab 2’s backup commander and was now mobilized to develop the extravehicular activity to free the stuck SAS-1 solar panel.

Utilizing tools procured from A.B. Chance, a company that made lineman-grade tools such as wire cutters, Schweickart and other astronauts (including Gibson and future “Buck Rogers” Bruce McCandless II) spent ample time devising contingency procedures and performing practice EVAs in Marshall Space Flight Center’s water tank located in Huntsville, Alabama. While a standup EVA performed by Skylab 2’s pilot Paul Weitz did not free up the stuck solar panel, a 3+ hour EVA performed by mission commander Charles “Pete” Conrad and science pilot Dr. Joseph Kerwin on June 7th ultimately did the trick – thanks to Schweickart’s research and development in the tank. If you’re reading this, you may be surprised Schweickart played such a massive role in Skylab’s revitalization and success because this story has never been publicized much. This is why he arguably hasn’t received much credit for this.

However, despite his success, he did not fly aboard any of the actual Skylab missions. He also viewed the Space Shuttle program as a non-starter for him (to be fair, many of the remaining Apollo astronauts at NASA viewed the Shuttle program with derision, including McDivitt and Apollo 15 command module pilot Al Worden, who titled a chapter of The Light of Earth “I Never Liked the Space Shuttle”). Schweickart, like McDivitt and Scott, decided to move into NASA management. In 1974, he was reassigned to NASA’s headquarters in Washington, D.C., as Director of User Affairs in the Office of Applications. He put his passion for protecting the Earth’s environment to work in this role. Having copious experience in diving and Earth observations (after all, he’d viewed the Earth from a unique spot during Apollo 9), he soon became involved in utilizing satellite technology to explore the world’s seas.

During August 1975, he – along with a crew consisting of oceanography legend Jacques Cousteau and President Gerald Ford’s son – conducted dives and research in concert with Landsat data. According to a NASA Landsat article written by Laura E.P. Rocchio, “For days, the [research vessel] Calypso played leap frog with the Landsat 1 and 2 satellites in the waters between the Bahamas and Florida, sailing 90 nautical miles each night to be in position for the morning overpass of the satellite. Ultimately, research done on the trip determined that in clear waters, with a bright seafloor, depths up to 22 meters (72 feet) could be measured by Landsat. This revelation gave birth to the field of satellite-derived bathymetry and enabled charts in clear water areas around the world to be revised, helping sailing vessels and deep-drafted supertankers avoid running aground on hazardous shoals or seamounts.”

The photos from this expedition also show Schweickart in his mid-1970s sartorial prime, with a mass of wild wavy hair that rivals Judy Resnik’s. More seriously, fellow diver and NASA’s then-Deputy Administrator George Low was also a big supporter of this project; in 1976, Low enthused, “It was a tremendous example of how modern tools of scientists can be put together to get a better understanding of this globe we live on.” This project arguably influenced other oceanography-facing satellite programs, such as JPL’s Seasat, which utilized synthetic aperture radar to make topographic maps of ocean floors, among other tasks.

Politics and Persuasion

During the decade, Schweickart also emerged as an early champion of Dr. Gerard K. O’Neill’s space settlement vision, which was also supported by fellow MIT graduate and Apollo astronaut Dr. Philip K. Chapman. A 1981 Christian Science Monitor profile sums up Schweickart’s thoughts regarding homesteading space: “For Schweickart, going into space is more than an opportunity to find a better dump to dispose of our garbage and a cheaper way to mine energy. He agrees with Freeman Dyson, the physicist and visionary thinker at the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton, that the world has a spiritual need for an open frontier and that the ultimate purpose of space travel is expansion of the spirit. ‘What expands our spirit is a larger vision and new horizons,’ Schweickart says.”

In a 2021 interview with this author, Schweickart recounted, “I thought the space colony concept was a pretty fantastic out-of-the-box (and into-the-cylinder!) idea. Far out, but with advanced technology, and a good bit more time than Gerry [O’Neill] allocated, a remote but possible future…Gerry was great! Very smart, very gregarious. Soft-spoken and thoughtful. He had no real illusions [about] the challenge of the concept, but felt that ultimately the technical challenges could be solved, and the concept needed championing, or it would never happen. So he risked his reputation to back a truly imaginative concept to open up the system…from the pragmatic point of view, foolish perhaps. But I don’t think he ever regretted his decision to go for it.”

By 1978, Schweickart had cut his long hair, tucked his t-shirts and flared jeans neatly into his dresser drawer, put on a business suit, and began the next phase of his career – this time in politics. He had been appointed as California governor Jerry Brown’s assistant in science and technology, focusing particularly on securing funding ($5.8 million specifically) for the Syncom IV communications satellite that the January 28, 1978 issue of The Fresno Bee optimistically described as being prepped to “launched with the Space Shuttle in 1980.” The article began with a rather hilarious description of the then 42-year-old Schweickart: “With an average build, lean features and thinning reddish hair, Rusty Schweickart doesn’t look like your basic $6 Million Man.” The newspaper went on to describe him as the “$5.8 Million Man,” a pun based on the ubiquitous television drama starring faux-stronaut Lee Majors (“A man barely alive…”). A March 19, 1978 profile of Schweickart in the Asbury Park Press featured an interview with his mother, Muriel, who mused with some relief, “We’ve always said he was a non-conformist. For instance, when everybody had their hair long he had it short. When they had theirs short, he wore it long. At least now it’s short again.”

All motherly concern over his hair length aside, Schweickart continued his political ascent, serving as chairman of the California Energy Commission under Governor Brown. Since the 1970s, Schweickart helped establish the Association of Space Explorers (ASE) and co-founded the B612 Foundation, an organization dedicated to planetary protection and asteroid mitigation. Again, when the foundation was established in 2002, the idea of redirecting an asteroid was something out of the movies Deep Impact and Armageddon – fun entertainment, looked cool in CGI graphics, but nothing rooted in real life; Schweickart’s vision, as usual, seemed fanciful. Fast forward to 2022, and NASA’s DART Mission proved that impacting an asteroid with a spacecraft could effectively alter its orbit – and thus prevent it from colliding with nearby objects such as planets.

Though they nearly got into fisticuffs over, yes, world peace, even self-described “old curmudgeon” Al Worden admitted he deeply admired NASA’s rebel with many causes. In The Light of Earth, Worden wrote:

I have to admit that he’s doing some of the most important work any astronaut has done after their space career was over. I admire him for this and thank him.

What if, one hundred years from now, a huge asteroid headed directly for Earth is deflected and humanity is saved – including my own descendants – as a direct result of Rusty’s tireless efforts?

This old curmudgeon is going to look pretty foolish for ever doubting him, isn’t he?

*****

Top photo: Astronaut Russell L. “Rusty” Schweickart in 1971. NASA photo.

A version of this article was published on Medium.

Emily Carney is a writer, space enthusiast, and creator of the This Space Available space blog, published since 2010. In January 2019, Emily’s This Space Available blog was incorporated into the National Space Society’s blog. The content of Emily’s blog can be accessed via the This Space Available blog category.

Note: The views expressed in This Space Available are those of the author and should not be considered as representing the positions or views of the National Space Society.