ISDC conference report by Dave Fischer

This is the first of two articles about the NASA Heavy Lift Vehicle program mandated by Congress.

Dan Dumbacher, Director of Engineering (NASA HQ)

Todd May, Associate Director, Technical (NASA MSFC)

Garry Lyles, Associate Director for Technical Management (NASA MSFC)

Dan Dumbacher introduced the panel by noting that NASA has been tasked with development of the next Heavy Lift Vehicle, and the folks at the Marshall Space Flight Center would like to get on with the job of building the next launch vehicle.

However, NASA’s budget is constrained by the current economy, and is likely to remain so for the foreseeable future. Indeed, it is likely to decrease somewhat over time.

The primary challenges in the confusing state of affairs revolve around the constituencies, as it always does in a political environment. The NASA Reauthorization Act of 2010, the 2011 budget from the administration, and the language of the compromise budget resolution for NASA in the summer of 2011 have all contributed to the muddled state of affairs.

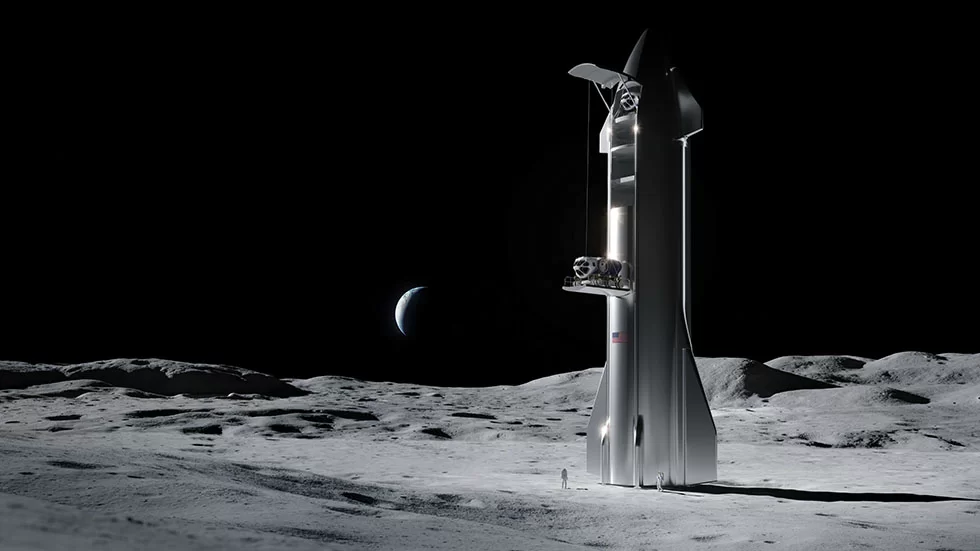

The current manned programs include the International Space Station and Commercial Cargo and Crew. The new beyond-low-Earth-orbit program will require new infrastructure, a new launch vehicle, a new spacecraft (such as the Orion – Multi Purpose Crew Vehicle), and ground support.

Todd May comes from the International Space Station project, certainly the most ambitious and complex international project ever conducted. Todd reviewed the results of the 13 heavy lift proposals received from industry. There is no magic rocket. However, cost was heavily influenced by NASA management and oversight practices as well as flight rate.

Garry Lyles then gave a detailed description of the work done over the past year on the heavy lift vehicle. Interestingly, he noted that he had spent time at a conference of building architects. They taught him that design beauty grew out of the requirements of the building, and that operational simplicity grew out of internal complexity.

He chose to test the concept of machine beauty with the Requirements Analysis Cycle (RAC). Three teams were created. One was devoted to Lox/H2, the second to Lox/RP and the third could choose either combination, but would focus on a lean manufacturing philosophy. Their results would be folded into the first two teams within the first half of the cycle. The final instructions to the teams were to be innovative and have fun.

The teams conducted several thousand parametric studies. One result was that many combinations would satisfy the physical requirements. By the end of the studies, the primary drivers of affordability, however, turned out to be lean systems engineering, stable requirements and simple organization. Reduction in development time was critical. Private industry knew that first to market with reduced cycle time meant lower people costs, which are a major component of overall costs. The subject of how NASA’s program might relate to Falcon Heavy was not addressed.

Difficult changes will be required from the traditional risk-averse NASA culture in order to accomplish these goals. It is going to be hard for NASA to adapt and adopt the key practices:

1. The machine will be complex, but the operation must be simple

2. Adjust the design in order to simplify the manufacturing process

3. Requirements must be early and stable

4. There must be margin in performance

5. Cycle time must be as quick as possible, but no quicker

6. Streamline the oversight of contractors

Without these cultural changes, it will be impossible for NASA to accomplish the heavy lift task in front of it.