This Space Available

By Emily Carney

Books still matter. Throughout the last sixty-plus years of spaceflight, literature chronicling spaceflight history and heritage – which run the gamut from detailing hardware and rocketry to describing the features of the Moon and various Solar System objects – have dazzled and awed readers, often introducing audiences to the subject. However, frequently the books that draw the most interest from readers are about the people – the astronauts, the flight controllers, and the workers. First person accounts of a particular period can function as a “time machine,” pulling the reader closer into a project’s or program’s orbit (pardon the pun).

This post will spotlight four books that defined one sub-genre in spaceflight literature – the astronaut (or, in one case, ex-astronaut) autobiography. These autobiographies are listed in chronological order, by publication date. While it would be impossible due to space and time constraints to list every astronaut memoir, these four titles are often cited as having inspired other astronauts and spaceflight personalities in his or her own storytelling endeavors.

The Making of an Ex-Astronaut, by Brian O’Leary (Houghton Mifflin Company, 1970)

This choice might be somewhat controversial, as Dr. Brian O’Leary, perhaps NASA’s most famous (or infamous?) ex-astronaut, doomed himself to a permanent exile from the fighter jock-heavy astronaut corps with the sentence, “Flying just isn’t my cup of tea.” But O’Leary’s 1970 sort-of-memoir mixed with op-ed essays, The Making of an Ex-Astronaut, was the first autobiographical work that began to lift the veil obscuring the astronaut corps during 1960s NASA. (Another work that would fully lift the veil will be discussed later in this list.) Moreover, it set the scene. You can envision a bespectacled O’Leary, age 27, walking around Houston’s Manned Spacecraft Center, looking bewildered, out-of-place, and anxious as he realizes he got himself waaaaaaaay in over his head with a job he can’t quite fulfill. Many of us have been exactly where O’Leary was at the time – except unlike us, his resignation would be broadcast all over the world.

O’Leary introduced several tropes that would become par for the course in astronaut autobiographies and spaceflight books, including ones on this list. For example, he “rated” his fellow 1967 “Excess Eleven” astronaut group colleagues, very much how Michael Collins rated his colleagues in Carrying The Fire. He detailed the selection process and candidates, which included a then-unknown, pre-High Frontier Princeton professor named Dr. Gerard K. O’Neill (who didn’t quite make the cut for this group). This “selection process” trope would be repeated to great effect in Tom Wolfe’s 1979 book, The Right Stuff. However, O’Leary – who had the benefit of youth and foresight when this book was written and published – turns the genre on its head, and soon we’re seeing how the realities and pressures of the job could be discouraging.

While he lingered a bit too long on how much he dislikes hot, sticky Houston (one whole chapter!), he made cogent points about how the astronaut cadre, focused on the singular task of landing on the Moon, made little effort in exploring the science of the Moon. Indeed, the Apollo lunar program only boasted three science-intensive missions, and those were tacked on at the program’s end. Near the end of his brief stint as one of America’s Newest Heroes, he’s receiving phone calls from horny “Cape Cookies” he’s never even met, and he’s crying in his car as he crosses a bridge to the ethereal strains of Simon and Garfunkel’s “Scarborough Fair,” terrified of going back to the NASA-mandated U.S. Air Force flight school. O’Leary goes resolutely against the grain of the archetypal mid-1960s Ken doll astronaut, and I am here for it. With this distinctly un-macho admission (that could be seen as embarrassing, particularly in 1970 as the United States was still savoring its Apollo 11 victory), O’Leary established another astronaut autobiography trope: the “come to Jesus” moment, when there’s no turning back from the truth.

As the book comes to its close, O’Leary begins to turn his vision to the futurism that would later spark a long collaboration with aforementioned O’Neill, the father of space settlements: “We should never lose sight of our ultimate goal in space: to understand nature and ourselves better by exploring the universe. The most exciting discovery to mankind may result from this exploration – the first contact with another intelligent civilization living among the heavenly bodies. …Even without a reply, we are summoned to travel through light years of cold interstellar space and discover the secrets of the planets circling the nearby stars.” These words predicted the visionary language that O’Neill and another working space scientist, Dr. Carl Sagan, would use within that decade.

While The Making of an Ex-Astronaut was criticized by many of O’Leary’s former colleagues and was not a massive success upon its release (perhaps aided by the public’s increasing lack of interest in spaceflight), this book did establish a template for future astronaut reminiscences, and for 1970s writing about futurism. While it is long out of print, you should track down a used copy, and read it to experience O’Leary’s – and NASA’s – 1967 world.

O’Leary’s age at publication: 30

Years resigned from NASA: Two-and-a-half

Carrying the Fire: An Astronaut’s Journeys, by Michael Collins (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1974)

O’Leary’s reminiscences may have introduced several now well-known tropes to the genre, but Michael Collins – of Gemini X and Apollo 11 fame – firmly established the template for astronaut autobiographies with 1974’s Carrying the Fire. Published five years after the first lunar landing and nearly two years after the Apollo Moon missions had ended, Collins’ descriptions of his selection, training, his colleagues, and his two space missions are fully engrossing and beautifully written.

Space historian Roger Launius wrote in a 2012 blog post, “It is a remarkably honest and reflective autobiography, and it extends a tradition of the aviator as litterateur into the age of space travel. Although written in 1974, and still available in inexpensive paperback editions, Carrying the Fire still has a freshness and crispness to it after some forty years.” Never before had an astronaut enjoyed a literary debut like this – Collins proved himself to be hilarious, spellbinding, and heartbreaking, sometimes within the limited space of a single page.

Few books can match Collins’ memories, five years removed, of the magnificent visions he saw during his jaunt as Apollo 11’s command module pilot. He wrote upon approaching the Moon, “The moon I have known all my life, that two‐dimensional, small yellow disk in the sky, has gone away somewhere, to be replaced by the most awesome sphere I have ever seen. To begin with it is huge, completely filling our window. Second, it is three‐dimensional. The belly of it bulges out towards us in such pronounced fashion that I almost feel I can reach out and touch it… The vague reddish‐yellow of the sun’s corona, the blanched white of earthshine, and the pure black of the starstudded surrounding sky all combine to cast a bluish glow over the moon. This cool, magnificent sphere hangs there ominously, a formidable presence without sound or motion, issuing us no invitation to invade its domain. Neil [Armstrong, Apollo 11’s commander] sums it up: ‘It’s a view worth the price of the trip.’ And somewhat scary too although no one says that.” Never before has a reader been so close to the Moon, and never before did an astronaut allow himself to be vulnerable enough to let us into his insular world, sans test pilot bluster.

However, Collins’ entry into the lunar lottery is nearly waylaid by a back injury that necessitates surgery. While this “come to Jesus” moment happens well before he’s inserted into Columbia atop a Saturn V in July 1969, at this point Collins establishes himself as a real writer with full command of language, and how it affects a reader. Check out his descriptions of the anesthetic haze he experiences, pre- and post-surgery: “Slice away, baby, I really didn’t care, and as they wheeled me into the operating room, I was only vaguely aware of very bright lights and some fool who wanted me to count backward from one hundred. I didn’t get very far… The next thing I remember is telling my wife a lot of very interesting things, but somehow her beautiful, sensitive face remained unaltered, impassive, as though she had not heard me. Finally, she drifted away, silently, and returned a long time later with Dr. Myers[.]” Collins straps the reader upon the operating table, helpless and prone, just as he pushes the same reader’s face ever so gently into face of the Moon. While history lets us know Collins made it through the surgery just fine, his writing puts us on the edge of our seats: will he recover? Will he ever be “normal” enough to walk again, much less go to space again?

While only a very limited number of human beings ventured to the Moon between 1969 and 1972, Collins made a journey to our closest natural satellite accessible to everyone with Carrying the Fire. Written in what he called “my chicken scratchings” on yellow legal pads in longhand, then transferred to type, this book remains the gold standard in astronaut memoirs. Carrying the Fire was reissued last year in celebration of Apollo 11’s 50th anniversary, is available through most major book retailers, and is essential reading.

Collins’ age at publication: 43

Years resigned from NASA: Four

Stay tuned for part two of this post, which will discuss two other genre-defining autobiographical works.

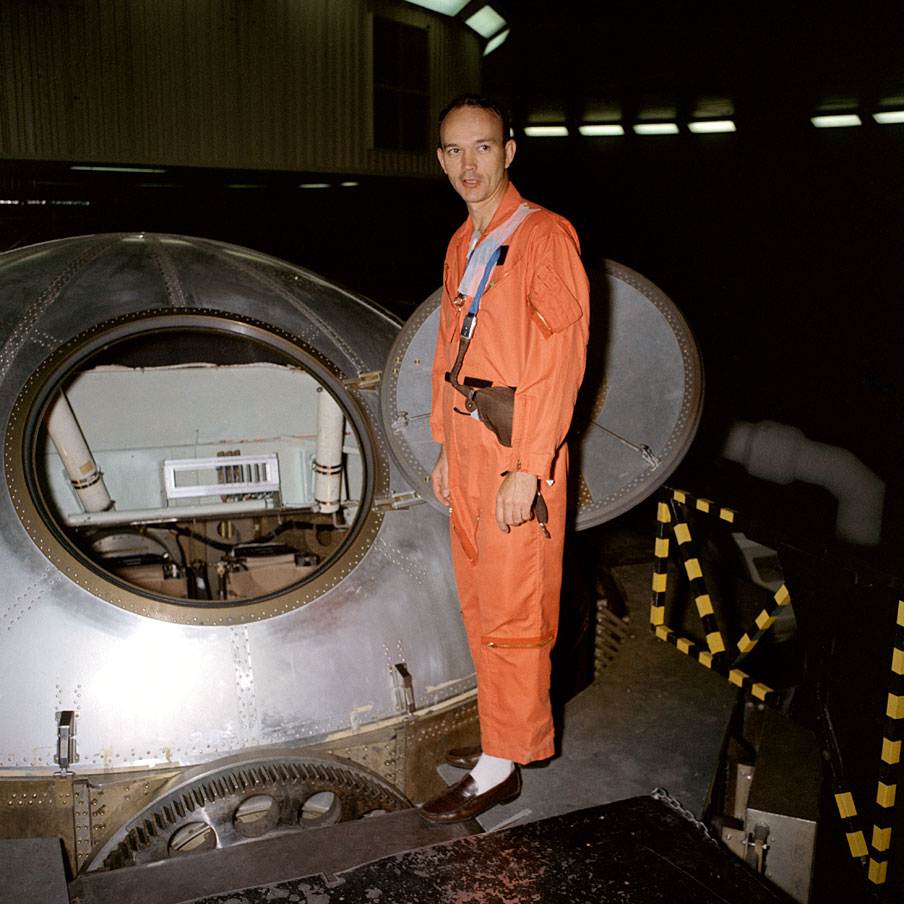

Featured Image Credit: Michael Collins before centrifuge training, 1969 Johnson Space Center scan. From the Project Apollo Image Gallery.

*****

Emily Carney is a writer, space enthusiast, and creator of the This Space Available space blog, published since 2010. In January 2019, Emily’s This Space Available blog was incorporated into the National Space Society’s blog. The content of Emily’s blog can be accessed via the This Space Available blog category.

Note: The views expressed in This Space Available are those of the author and should not be considered as representing the positions or views of the National Space Society.