Category: Non-Fiction

Reviewed by: Marianne Dyson

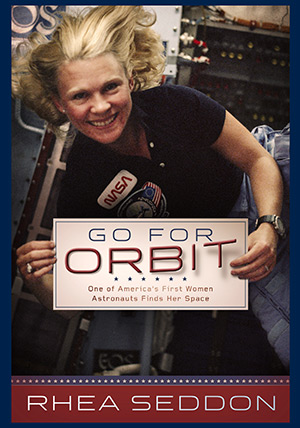

Title: Go for Orbit: One of Americas First Women Astronauts Finds Her Space

Author: Margaret Rhea Seddon

NSS Amazon link for this book

Format: Kindle

Pages: 224

Publisher: Your Space Press

Date: April 2016

Retail Price: $14.99

ASIN: B01EAZN5NO

Born in Murfreesboro, Tennessee, Rhea Seddon was raised as a southern lady, complete with ballet and piano lessons. Like many children growing up during the Apollo era, she was fascinated with space. When she set herself the goal of becoming a surgeon, she had no idea that she would make history as one of the first women to fly into space.

She was in the last year of her residency in 1977, single, exhausted, covered in blood from yet another gunshot victim at a hospital emergency room dubbed “the pit” in Nashville, when she found out that NASA was recruiting women to be Space Shuttle astronauts. She applied, but didn’t tell anyone for fear of being laughed at.

Seddon writes about answering the surprise “call” asking her to come for an interview, agonizing over what to say in the required essay, the sexist questions she was asked, and the awkward handling of her first contact with the news media.

After selection in 1978, she and the other five women were dunked and dropped and scrutinized for any weaknesses compared with the military pilots whose motto was “Better dead than look bad.” She endured it all. But she writes, “I soon learned that my biggest problem as an astronaut was not being female: it was being small.” The step to get into a T-38 was at her waist level and the smallest parachute available was so wide at the shoulders that she risked sliding out in an emergency. During training, she nearly suffocated because of a too-large space suit.

Physical strength and endurance presented challenges as well, especially requirements for SCUBA certification which she had to meet despite being too small to be considered for an EVA. She practiced with dogged determination at a community pool until she could tread water for 20 minutes, swim underwater two lengths of the pool, and retrieve a brick from the deep end.

Hundreds of color photos and overviews of shuttle systems make it easy to follow Seddon’s experiences.

After the success of STS-1 in 1981, Seddon and fellow astronaut Robert “Hoot” Gibson became the first American astronaut married couple. About a year later, when she told NASA she was pregnant, they grounded her from flying T-38s despite no evidence that it would cause any harm. She recalls worrying, “If they thought I was too ‘disabled’ to fly the jets, what other things were in store?… Would they write me off when it came to flight assignments because I had a young baby at home?” She was determined to prove that women could have children and still do their jobs.

Thus Seddon felt compelled to rush back to work six weeks after giving birth via C-section. “I learned a lot from that experience, mostly that young moms need more than six weeks to bond with their babies. Other stuff, even the important things like the space program, can wait a while.” She describes her first year as a new mom while supporting her husband’s first flight and training for her own, plus working in the ER every weekend, as “insane.”

Seddon’s first flight was supposed to be STS-41F in the summer of 1984. But schedule changes led to it being cancelled, and as a result she lost the chance to be the first mother and third American woman in space. Those honors went to Anna Fisher instead. She was assigned to STS-51E which flew in April 1985. The flight deployed Syncom which failed to activate. Showcasing the value of humans in space, Mission Control authorized an unplanned spacewalk to mount a makeshift “flyswatter” to the arm (controlled by Seddon) in a valiant though unsuccessful attempt to recover the satellite.

The Challenger accident in 1986 had an enormous impact on everyone involved with the space program, and most especially on the astronauts. Seddon’s very personal account of washing her friend Mike Smith’s flight suit by hand (so he could be buried in it) should become required reading for anyone involved with launch go/no-go decisions.

The accident postponed the Space Life Sciences (SLS) Spacelab flight that Seddon had been training for. Her choice between an earlier flight assignment in 1988 and a chance to have another baby while she still could (at age 40), will resonate with many professional women today. Some people may be surprised to learn that she opted for the baby (born in 1989).

Seddon flew on two Spacelab flights: SLS-1/STS-40 in June of 1991, and SLS-2/STS-58 in October 1993. Her description of the medical experiments conducted on her flights, including the political issues involving the animal experiments and details about the effects of re-adaptation, are refreshingly frank and not something readers are likely to find in any other space books.

The final chapter recounts the effects on the Astronaut Corps of the decision to partner with Russia on Mir and the International Space Station. Though she’d faced and overcome many challenges to become one of the first female astronauts, she didn’t relish learning Russian and spending months away from her children in another country to fly on assembly missions. So she left NASA in 1996 and returned to medicine and Tennessee. “No one could take away from me the experiences I’d had…. No one could any longer say that women couldn’t be astronauts. It seems strange looking back that it was ever doubted.”

I recommend this inspiring book to everyone. This is not just a woman’s story or a space story. It is the story of a remarkable human being who faced down the naysayers, stood up to physical and emotional challenges, sacrificed personal gain for the good of others, and went on to live happily ever after. It just doesn’t get any better than this!

© 2016 Marianne Dyson

Please use the NSS Amazon Link for all your book and other purchases. It helps NSS and does not cost you a cent! Bookmark this link for ALL your Amazon shopping!