Reviewed by: Loretta Hall

Title: Amazing Stories of the Space Age

Author: Rod Pyle

NSS Amazon link for this book

Format: Paperback/Kindle

Pages: 365

Publisher: Prometheus Books

Date: January 2017

Retail Price: $18.00/$11.99

ISBN: 978-1633882218

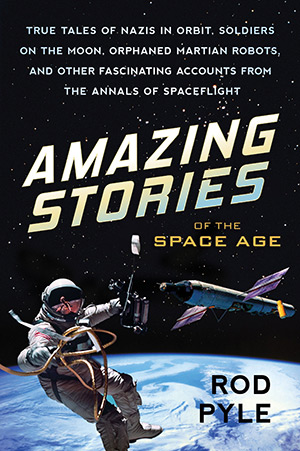

This book’s lengthy subtitle emphasizes just how amazing some of these stories are: “True Tales of Nazis in Orbit, Soldiers on the Moon, Orphaned Martian Robots, and Other Fascinating Accounts from the Annals of Spaceflight.” That’s quite a mouthful, but it’s an accurate preview of the strange tales in Rod Pyle’s new book. Many of the more outlandish ones were, thankfully, only conceptual. Those Nazis never made it to orbit, although the plans were worked out in detail. German soldiers would have lived aboard a satellite equipped with a sunbeam-focusing mirror that could produce a devastating heat ray. Plans even included growing pumpkin plants aboard the satellite to generate oxygen for the crew.

The early space age (1950s and 1960s) dominates the timespan of the stories, although a few extend into the twenty-first century. In some cases, Pyle lets us in on events and plans long shrouded in secrecy. Of the twenty-two chapters, eleven had been classified at some point. Some were declassified as recently as 2015.

One example is the U.S. Army’s Project Horizon, which was initiated in 1959 and declassified in 2014. The project laid out a timeline by which a military base on the Moon would be operational by 1966. The base would enable surveillance of the Soviet Union, and it would be equipped with nuclear weapons that could be launched at targets on Earth as a deterrent to Soviet aggression. Pyle acknowledges the impracticality of a deterrent in the form of missiles that would take two days to reach their targets on Earth. But he also places the project into the context of the early space era: “At the time, missile guidance systems and flight robotics were still in their infancy. Earth-observation satellites such as those fielded in the 1960s, which could deliver images of Soviet territory within a few days of launch, were nonexistent. There were no submarine-launched ICBMs, no instant high-altitude overview of enemy activity so space was the classic ‘high ground’ armies have sought throughout history.” He fleshes out the military nature of the Moon base with descriptions of the weapons that could be developed for its defense. One would be an anti-personnel mine deploying a shower of pellets designed to puncture the enemies’ space suits. “The pellets didn’t have to kill the enemy [M]oon soldier; the vacuum of space would do that.”

Another proposed project that now sounds bizarre was Project Orion, which was conceived in 1955 and refined in 1958 with funding from the Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA). In its final version, a large, manned spacecraft would be propelled by a continuous series of nuclear explosions. The upper portion of the vessel was to hold crew quarters and supplies. Pyle explains that “the bottom half was fuel (bomb) storage and a shock-absorbing system—really big, heavy-duty shock absorbers—capable of converting the 10,000 g, crushing propulsive blasts into survivable acceleration by absorbing and gradually releasing all that energy.” Injecting his characteristic humor, Pyle explained that “for liftoff they would have to detonate smaller bombs more frequently—at least one 0.1 kiloton bomb per second. And yes, they were going to do exactly what you are probably thinking—they would launch their atomic monster from Earth. Bang, bang, bang. Sorry you have cancer—we’re on our way to Saturn.” The plan was discarded in 1959.

Many of the chapters introduced me to actual plans for endeavors I had never heard of, like those just mentioned. Other chapters provided more detailed information than I had previously seen about more familiar events. One example is the Apollo 11 Moon landing. I knew that the successful landing was plagued by computer problems and near depletion of fuel. Then I learned a frozen blockage in a fuel line caused by the Moon’s extremely cold surface raised fears of a potentially explosive pressure buildup. Later, the astronauts had trouble opening the hatch to begin their EVA because of residual air pressure after venting the lunar module. Pyle writes, “Aldrin eventually resorted to tugging on one edge of the front hatch. It was so thin that there was a bit of flex, and that was enough to vent the rest of the air into the lunar void.” Aldrin’s description of the door as being “fairly flimsy” is a sobering observation that reminded me of just how dangerous the Apollo Moon missions were—something many people tend to forget these many decades later.

Some of Pyle’s “amazing stories” fall into the stranger-than-fiction category, and others illustrate the technical complexities and political intricacies of the early space age and the Cold War. All are interesting, both intrinsically and because of Pyle’s engaging writing style.

I recommend this book for science fiction fans as well as human-spaceflight enthusiasts.

© 2017 Loretta Hall

Please use the NSS Amazon Link for all your book and other purchases. It helps NSS and does not cost you a cent! Bookmark this link for ALL your Amazon shopping!