Category: Non-Fiction

Reviewed by: Loretta Hall

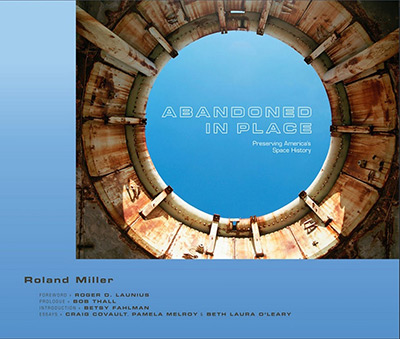

Title: Abandoned in Place: Preserving America’s Space History

Author: Roland Miller

NSS Amazon link for this book

Format: Hardcover/Kindle

Pages: 176

Publisher: University of New Mexico Press

Date: March 2016

Retail Price: $45.00/$29.95

ISBN: 978-0826356253

This well-produced coffee-table book is filled with starkly beautiful photographs that evoke bittersweet memories contrasting America’s “glory days” of space exploration with the abandoned remnants of infrastructure that made them possible half a century or more ago. The oversize book fills the reader’s lap with words and with images that surpass words.

“I titled my project Abandoned in Place because those words are stenciled on many of the deactivated facilities at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station,” Roland Miller writes. “To me, ‘abandoned in place’ is an obvious metaphor for the abandonment of our manned space-exploration efforts and for the public’s loss of interest that occurred after the first few Moon-landing missions.”

By profession, Miller is a photographer and dean of the Communication Arts, Humanities and Fine Arts Division at the College of Lake County in Grayslake, Illinois. He is also a dedicated space buff. As a child during the 1960s, he was fascinated by science-fiction-turned-reality, and as an adult, he says he was “hooked” when he saw his first rocket launch in 1984. A few years later, when he was helping with disposal of old photographic chemicals at Cape Canaveral, he was struck by the “ruins of early space flight” and committed himself to documenting them.

The book’s subtitle, Preserving America’s Space History, apparently refers to preservation through Miller’s photographs because neither NASA nor the US Air Force is preserving these structures physically. The photos show extensive rust, peeling paint, cracks, and other signs of deterioration. Some structures have been demolished or salvaged, but those that would be too difficult or costly to tear down have simply been “abandoned in place.”

The exception to that interpretation of “preserving America’s space history” is an essay contributed by Beth Laura O’Leary, a professor emerita of anthropology at New Mexico State University. She is a leader in the effort to establish procedures for protecting manmade objects on the Moon, Mars, Venus, and other celestial bodies. These include not only items like lunar module descent stages and debris from impact probes, but also footprints and lunar rover tire tracks. She argues for the importance of preserving “190 metric tons of material culture, which we have placed there [the Moon] since 1959.”

O’Leary’s essay is one of six that augment Miller’s text and photographs. Art historian Betsy Fahlman, for example, offers historical background and an explanation of industrial archaeology. She writes, “Documentation of the immense industrial artifacts from the space age, now rusted and worn examples of ‘Dead Tech,’ allows an observer to look at the roots of twentieth-century space travel and exploration…. Such remains not only speak eloquently of an emphasis and effort not since duplicated, but they also give viewers a glimpse of the urgency and importance of the technology and its time.”

Space shuttle astronaut Pamela Melroy’s essay describes her emotional attachment to Cape Canaveral’s Launch Complex 34, where the Apollo 1 astronauts perished in a fire during a launch simulation. “For me, Pad 34 is and always will be a completely unique place in the heart of a bustling spaceport—a quiet place to think and a spiritual place to meditate,” she writes. “I feel the past there, but very much as a part of the present. I feel the spirit of my heroes reaching across time, guiding and shaping all that we do in human space flight.”

Melroy’s comments echo Miller’s sentiments. He describes one of the days he went to photograph Launch Complex 34. As he huddled in his car, waiting out a booming thunderstorm, his thoughts ranged over the explosive successful launches conducted there as well as the Apollo 1 tragedy. When the storm passed and he got his camera equipment out of the car, he was overcome with emotion. He took only one good photograph. “I tried to make several more images, but they felt hollow, pointless,” he writes. “The storm, the history, the accomplishments, the tragic loss overwhelmed my senses.”

Fortunately for us, Miller visited Pad 34 and other historic sites often enough to produce an impressive collection of images showing massive structures and intimate details, melancholy moods and inspiring vistas. His book helps us preserve monuments and memories of America’s space history.

© 2016 Loretta Hall

Please use the NSS Amazon Link for all your book and other purchases. It helps NSS and does not cost you a cent! Bookmark this link for ALL your Amazon shopping!